The Hewlett Packard EliteDesk 800 G1 Mini PC is a tiny desktop computer with lots of big features!

The Hewlett Packard EliteDesk 800 G1 Mini PC is a tiny desktop computer with lots of big features!Its footprint is 6.9 x 1.3 x 7.0 inches and it weighs only 2.92 pounds, less than a lot of laptops! The HP EliteDesk 800 G1 Mini PC has a 4th generation Intel processor and runs the newest Windows operating systems. The front of the computer includes two USB 3.0 ports (one of which is a USB fast charge port) and an audio-out and microphone jack.

|

| Shown with optional stand, monitor, keyboard and mouse |

On the back, it has an additional four USB 3.0 ports, a VGA connection, an Ethernet port, 2 Display Ports, and an audio-out jack. The bottom of the HP EliteDesk 800 G1 Mini PC has a VESA mount.

A wireless card is an option as is an external DVD/RW drive. With a 500GB standard hard drive or up to a 1TB solid state drive, the HP EliteDesk 800 G1 Mini PC packs a great computer into a "mini" package. Also, due to its small size, it has more than 3 times the energy-efficiency of a tower desktop.

The unit I received has a 2.9gHz i5 processor and is running Windows 7 Professional, but the upgrade disk to Windows 8.1 was also included in the package. It has 4GB RAM, a 128GB solid state hard drive, and the WiFi card.

Here is more detailed specs and information about the HP EliteDesk 800 G1 Mini PC.

USE IN SCHOOLS

In the education arena, the HP EliteDesk 800 G1 Mini PC can solve any number of problems as well as help schools think “out of the box”.

Teacher’s desks are notoriously cluttered with the tools of the trade…their teaching materials, stationery supplies for student use, and much more. The diminutive footprint of the HP EliteDesk 800 G1 Mini PC can free up a ton of usable space on a teacher’s desk and also eliminate the “big box” on the dusty floor! Teachers can easily get access to the USB ports and audio jacks on the front of the EliteDesk G1 Mini PC when they need to, too.

Another plus for teachers is the WiFi capabilities of the device. In the past, teachers were tied to classroom area of the Ethernet jack and VGA connection. Now, with wireless projectors and wireless network access, the HP EliteDesk 800 G1 Mini can sit anywhere in the room. In addition, with the plethora of collaborative apps that can have students share over WiFi, the teacher and students can share documents, collaborate in real-time on virtual whiteboards, and students can mirror their mobile devices to the teacher’s desktop.

In schools where security of computers in a lab setting or classroom is a concern, this tiny HP EliteDesk Mini 800 G1 Mini PC can be easily locked up at night in a drawer or closet. It does have the traditional cable lock port, but locking them up at night might be a better option.

The low cost and energy-efficiency also make this mini computer a perfect replacement for the bigger CPUs in a computer lab setting. The SSD drive makes them fast to boot up and, again, space is saved on the computer lab tables for other student project-based or reference work.

One creative idea, if students have a monitor, keyboard, and mouse at home, is to have the HP EliteDesk 800 G1 Mini PC become a school’s 1:1 device of choice. The light 2.92 lb. weight, the SSD drive which would not be subject to problems when carried in a backpack, and the built-in WiFi could allow students to bring it back and forth from school to home. In school, there would be labs of monitors, keyboards, and mice and extra sets of these in the classroom, library, science labs, and even the cafeteria! A student would just hook-up his or her HP EliteDesk 800 G1 Mini wherever there was a “workstation” spot.

THE CONTEST

HP graciously provided me with the opportunity to give away a new HP EliteDesk 800 G1 Mini PC to a lucky US or Canadian PreK-16 educator or pre-service or graduate education student! In order to have a chance to win the Mini PC, educators were asked to make a mini-- a mini-infographic that is!

As you know, an infographic is a visual representation of data. Having students create them as a formative or summative assessment can help them practice their information literacy, visual literacy, data literacy, and technology literacy skills.

When starting off with this type of lesson or unit, it is best to start small. Have students research to find one piece of interesting data, decide who the audience for the infographic is going to be, consider the type of data visualization that would work best to showcase the information, and then create a mini-infographic showcasing just that single piece of interesting data.

USA Today, since beginning publication, has offered a mini-infographic they call a “snapshot” on the front page of each issue of the newspaper. Researchers, reporters, and editors in each of the primary departments of News, Money, Sports, and Life account for most of the ideas and research for these snapshots. Once the research is complete, the information goes to a graphic artist who creates the infographic. This process usually take between three and four hours.

Here are some links to sample USA Today snapshots in the area of news.

- http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/snapshot/news/2001-07-02-gas-prices.htm

- http://images.usatoday.com/graphics/snap/news/julygas.jpg

- http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/snapshot/news/2001-07-06-familysize.htm

- http://images.usatoday.com/graphics/snap/news/familysize.jpg

- http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/snapshot/news/2001-04-24-email.htm

- http://images.usatoday.com/graphics/snap/news/emailnews.jpg

- http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/snapshot/news/2001-08-13-cellphone.htm

- http://images.usatoday.com/graphics/snap/news/n.cellphone.jpg

- http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/snapshot/news/2001-09-11-america.htm

- http://images.usatoday.com/graphics/snap/news/america.jpg

CONTEST OVERVIEW (CONTEST CLOSED DECEMBER 7, 2014)

In order to participate in the contest to win an HP EliteDesk 800 G1 Mini PC desktop computer, the educator had to create a mini-infographic or “snapshot” and submit it to me. The winner of the HP EliteDesk 800 G1 Mini PC was randomly chosen from those educators who submit the mini-infographic.

The topic of the infographic had to be in their content area, an education or educational technology-related topic, or anything else of interest to K-12 educators or students. The infographic could have been intended to inform or persuade. I provided the entrants with the background image to use for the infographic.

To find out more about infographics, visit my infographics page here: http://www.schrockguide.net/infographics-as-an-assessment.html

CREATING THE MINI-INFOGRAPHIC

The easiest way to create a mini-infographic is to create a single slide in PowerPoint, Keynote, or Google Slides. For this contest, I had created a PowerPoint, Keynote, and JPEG version of the background entrants were required to use. The background illustrated the "clean" desk teachers would have by using an HP EliteDesk 800 G1 Mini PC!

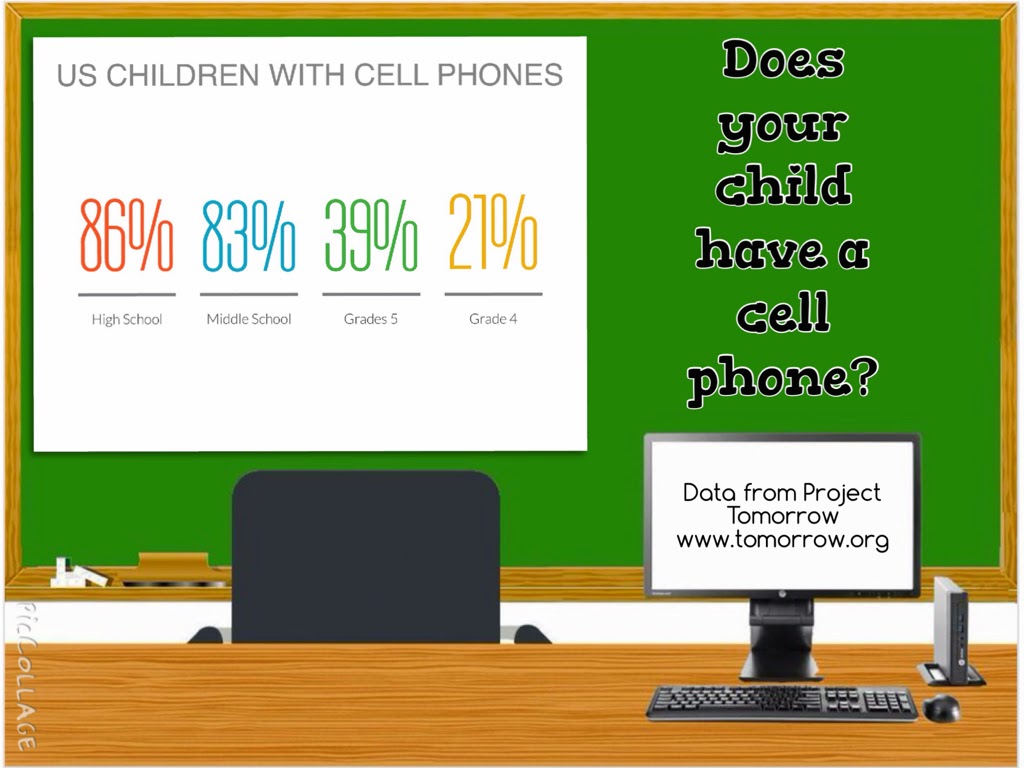

On that single slide/image, entrants had to add the text and data information, and include the citation to the sources used for their infographic information. All of that information had to be that single slide. Here is a sample I created:

When entrants were finished with the slide, in PowerPoint they picked FILE- SAVE AS PICTURES, in Keynote picked FILE-EXPORT TO- IMAGES, and in Google Slides picked FILE- DOWNLOAD AS- JPEG IMAGE. They saved the image to their desktop or Google Drive (or their Camera Roll or Gallery if they were using a tablet).

Entrants emailed the single JPEG image to me at kathy@kathyschrock.net. They also put "Mini" in the subject line of the email and their name, email address, and Twitter handle (if they had one) in the body of the email.

Here were the links to the background image in the three different formats

REVIEW

Educators had to locate some small bit of data they wanted to share with other educators or students. Using the background on the single slide, they added --

- a title for the infographic

- a labeled chart or graph

- text to explain what the viewer is seeing

- URL to the page(s) where they obtained the data

- Saved the slide as JPEG to their computing device

- Sent the JPEG as an attachment to kathy@kathyschrock.net with the subject of "Mini"

- Included their name, email address, and Twitter handle, if they had one, in the body of the email

By submitting the mini-infographic entry, entrants had a random chance to win the HP EliteDesk 800 G1 Mini PC and they were giving me permission to possibly post your infographic on my blog site whether they won or not. Their name would not appear on the Web page, just the mini-infographic itself.

By submitting the entry, if they were chosen as the winner, they were are also allowing me to share their name, email address, and mailing address with HP (or an HP associate) so they could send the winner the HP EliteDesk 800 G1 Mini PC.

The winner’s name would be announced on the blog (but not tied to their submission) and on Twitter.

The email address of all who submit entries will remain private except for the winner, whose email address will be shared with HP (or an HP associate).

The submissions were due on: December 7, 2014 by 11:59 PM Eastern Time and the contest is now closed.

UPDATE DECEMBER 8, 2014

SUBMITTED INFOGRAPHICS

Here are some of the great mini-infographics that were submitted! Thank you to all who re-tweeted about the contest and for those that submitted an entry!

THE WINNER

The randomly-chosen winner of the giveway of the HP EliteDesk 800 G1 Mini PC was Mark Case! I used the DecideNow app on the iPad to pick the winner-- congrats to Mark!